Once you know these, you can’t unknow them, and you will see them in all kinds of published theses and dissertations (including my own, oops!).

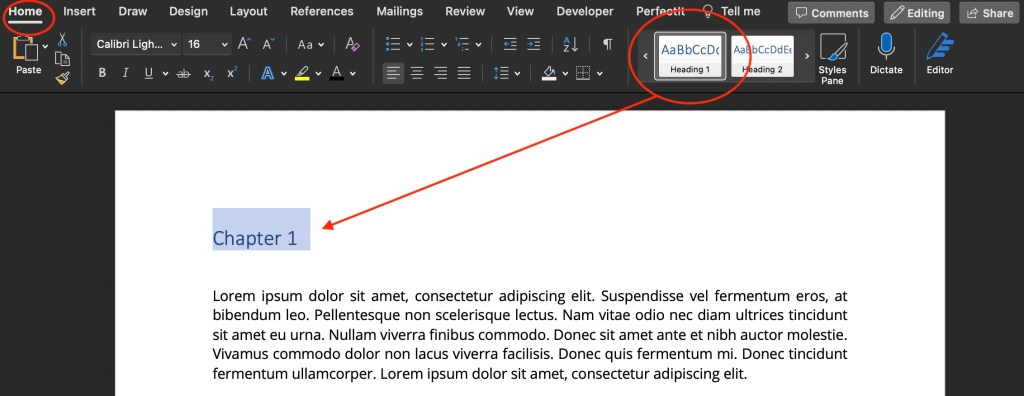

Tip #1

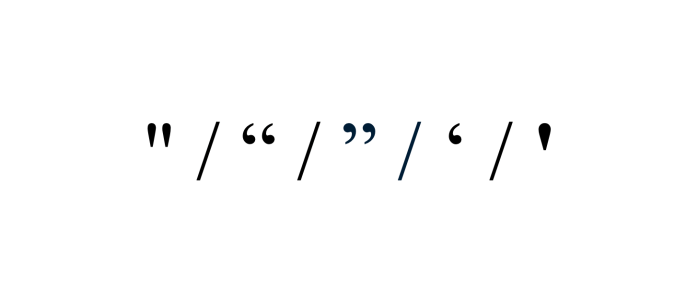

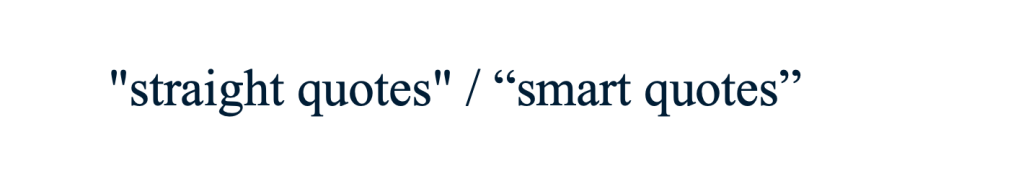

Problem: A mix of smart quotes and straight quotes

Straight quotes look the same whether they open or close a quotation and are a holdover from the typewriter. Smart quotes are the curly quotation marks that indicate the opening or closing of a quotation.

Often, when we cut and paste quotes from the web or other sources, we can unwittingly bring the local formatting into our documents, causing straight quotes to show up where they shouldn’t.

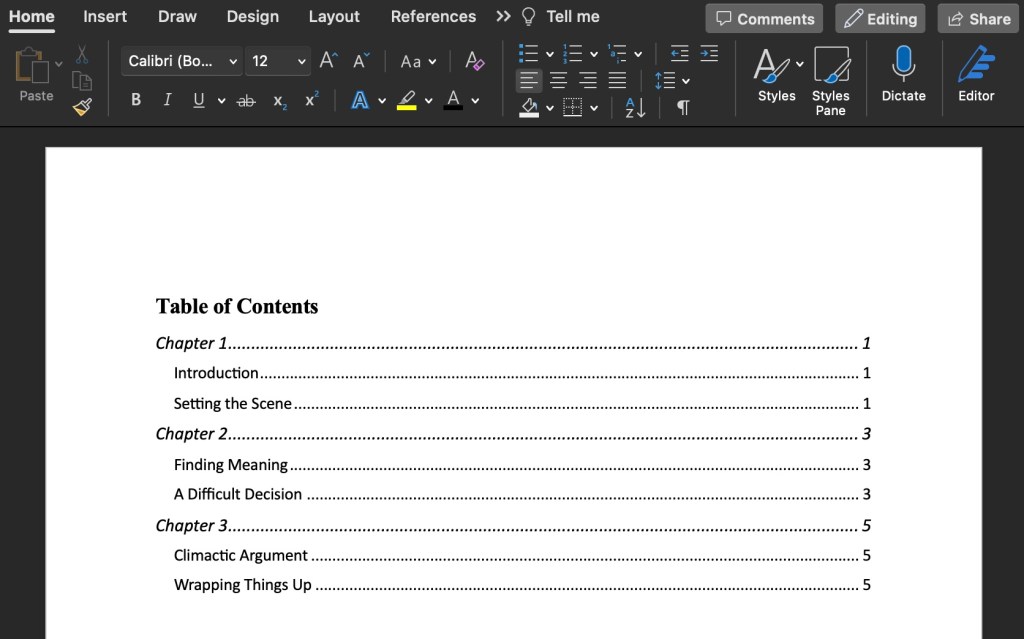

Fix: Find and Replace All

Word is set to automatically use smart quotes, so all you have to do is put a quotation mark into “Find” and a quotation mark into “Replace” and select “Replace All.”

Word will replace all the quotation marks with smart quotes whether they were originally straight or already smart.

You can do this with apostrophes as well.

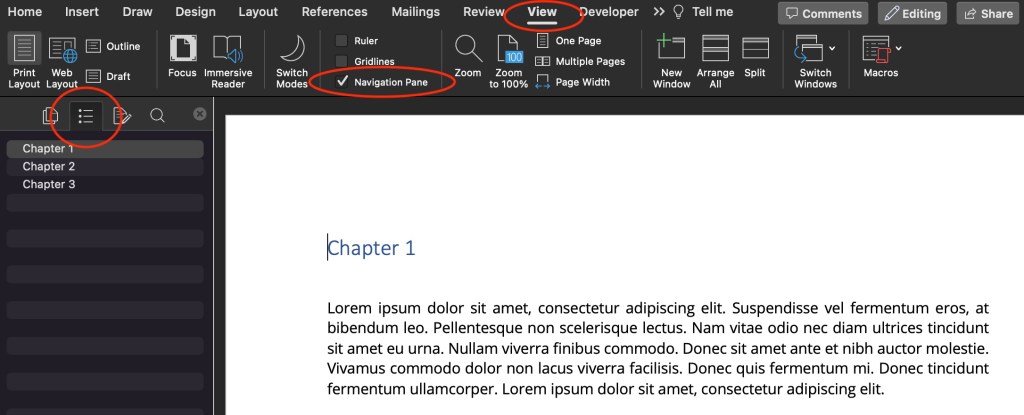

TIP #2

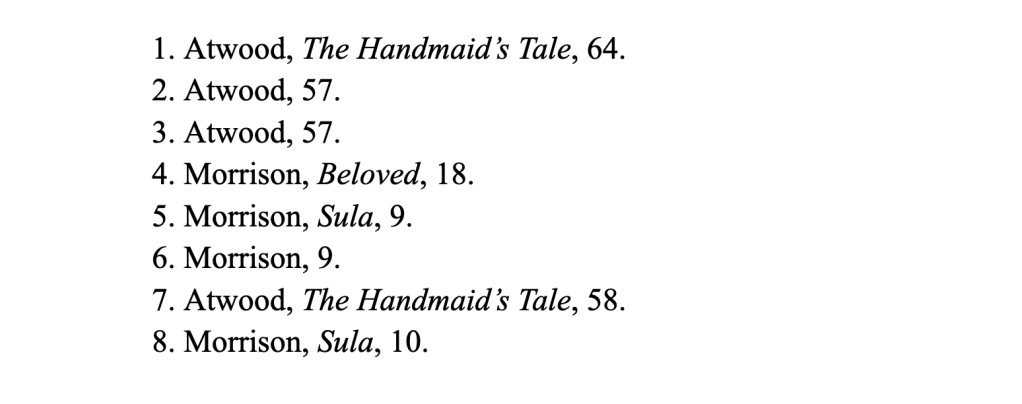

Problem: Italicized commas after italicized words

Can you spot the difference?

Commas following italicized titles, such as The Color Purple, should be consistent with the punctuation of the surrounding text (as it is here).

It can be difficult to notice the difference between an italicized comma and a regular comma if you’re not looking for it, but now you’ll see this everywhere, and it will bug you. You’re welcome.

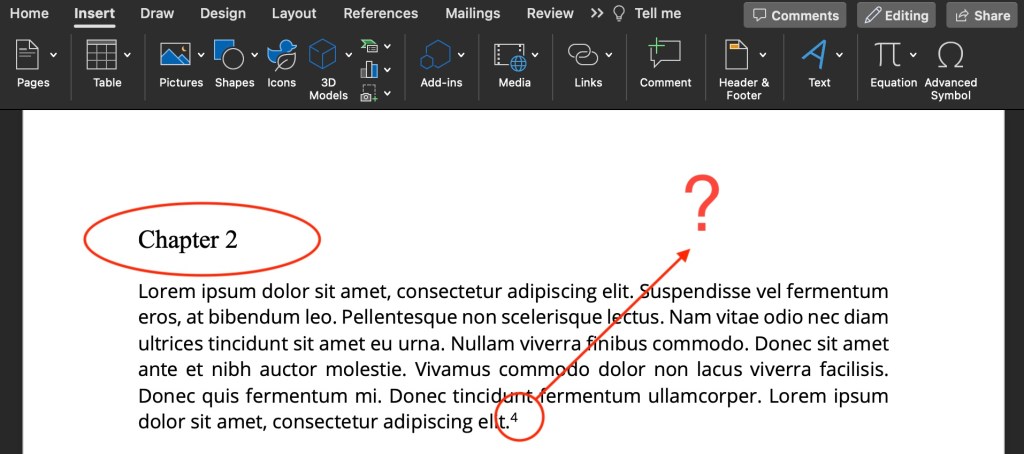

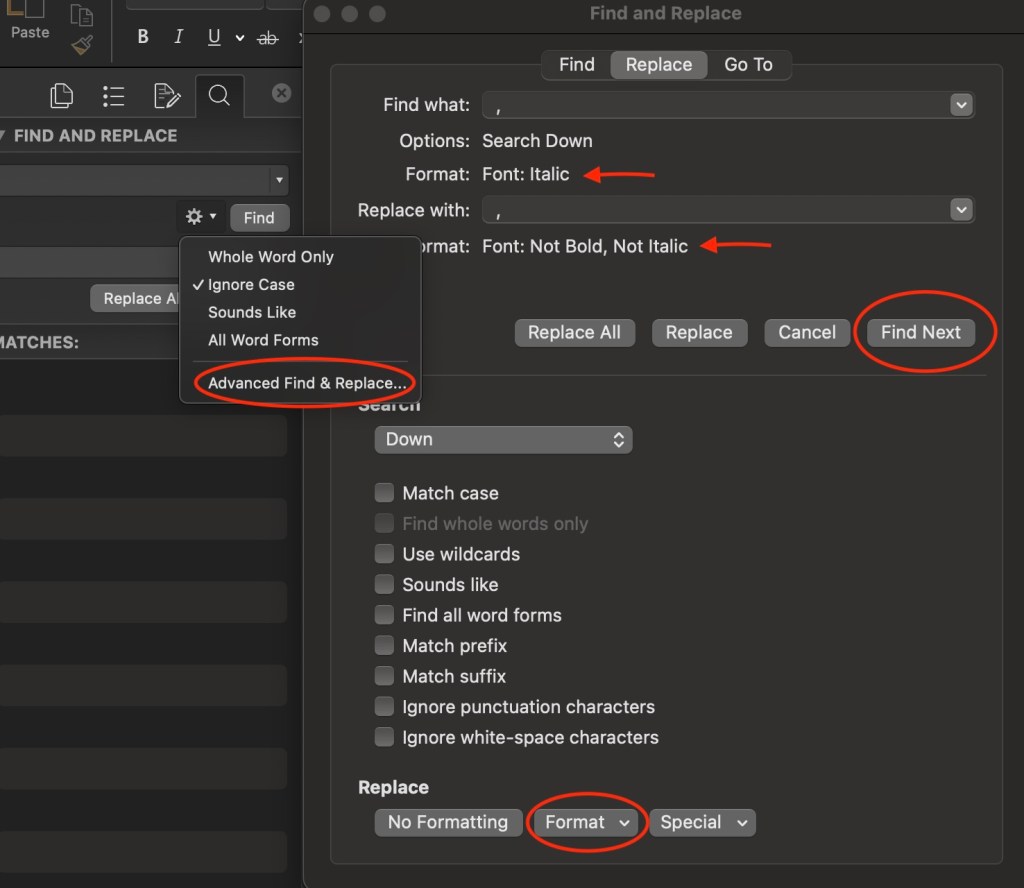

Fix: Advanced Find and Replace

Under Advanced Find and Replace, type a comma in the “Find what” field.

Then use the dropdown and select Format > Font > Font Style > Italics

Under the “Replace” tab, type a comma in the “Replace with” field.

Then select Format > Font > Font Style > Regular

You can’t use “Replace All” for this fix. Rather, you will have to decide whether or not to replace each instance individually, because there may be cases where the italicized comma should remain, such as when the comma appears within a title or italicized passage.

If you have any trouble executing these tips, please let me know here!